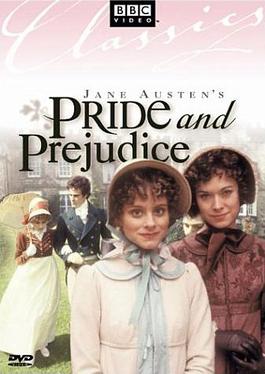

As many of you may know, today marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Jane Austen's classic novel Pride and Prejudice. Therefore, it only seems fitting to write up today a post I've been thinking about for some time. If you guessed that this post would be about Pride and Prejudice, you would be right. But you'd also be wrong. For this post is going to address two BBC miniseries that came in the 1980s - the first one is 1980's Pride and Prejudice and the second is 1983's Mansfield Park.

The BBC's 1980 miniseries of Pride and Prejudice seems to be one adaptation of the novel that has been largely forgotten. I hardly ever hear about it, for Austen fans seem to flock either to a feature film version - generally more watered down but also an easier thing to digest, especially in one sitting - or to A&E's 1995 miniseries, which seems to have positioned itself as the screen version of the Pride and Prejudice story. However, this miniseries does a pretty good job at adapting the novel, even if it is now overshadowed by the one starring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth.

If you don't know the story of Pride and Prejudice, that can only be because you haven't read the book and you should do so immediately! :) But here are the basics for those of you who aren't well-versed in Austen's novel: In Regency England, there lives a family consisting of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters. Because the law at the time would not leave estates to women and working was an unheard of thing for gentrified ladies, the five young women will be hard off, to put it lightly, when their father dies. That is, unless they can marry well. Enter their village's latest resident, the wealthy Mr. Bingley who comes accompanied by his good friend, the even wealthier Mr. Darcy. Bingley is immediately charmed by the eldest Bennet daughter, Jane, while Darcy snubs his nose at her sister Elizabeth. But as Shakespeare says, the course true love never did run smooth, and these first impressions aren't everything. We're taken on a roller coaster year as the Bennet sisters search for happiness and love.

The casting of the 1980 Pride and Prejudice miniseries is for the most part quite spectacular. In particular, Sabina Franklyn as Jane Bennet looks and acts exactly like the darling sweetheart you except her to be, and it may be heretical for me to say, but I actually preferred David Rintoul as Mr. Darcy over Colin Firth in the role. Some criticize Rintoul as too wooden and stiff in this miniseries but quite frankly, that's who Mr. Darcy is. He is someone who has a tough time letting his hair down, so to speak, and enjoy himself in the society of others, especially at large gatherings. (Come to think of it, Mr. Darcy is pretty much the definition of an introvert, even though everyone else around him decides his manners show an air of superiority and too much pride in himself.) I really enjoyed that the actor playing Lady Catherine de Bourgh was

much younger than ones I've seen in the role previously; I think that

helped to make her feel less like a bitter old maid and more

like the ridiculously snobbish person who she is.

When Elizabeth Garvie first appeared on the screen as Elizabeth Bennet, I wasn't so sure I would like her, but she grew on me pretty quickly and I came to enjoy her performance, with a few exceptions (more about that later). The rest of the Bennet sisters looked and played their parts quite well, but I was somewhat disappointed in their parents. This particular rendition of Mrs. Bennet was a little too over the top for me at times while Mr. Bennet came across as rather cold. Some of that may be more in the scripting than the acting, but I'm inclined to think it was a combination of both. I was a bit disappointed in the casting of George Wickham, as I generally am, for most versions don't seem to find someone so very attractive and dashing as to woo the whole town as Wickham does. Some of the seductive qualities might have been lost in the scripting as well as the acting, but I'm once again inclined to think both are at work here, if not more so the latter. Nearly all the rest of the characters, including Mr. Bingley, Miss Bingley, Charlotte Lucas, Mr. Collins, and so on, were very convincing in their roles.

Because it was 1980 and this was a made-for-TV production, this miniseries doesn't have the fine veneer of polish that we're accustomed to these days. Sometimes the production quality is quite low, with overwhelming lighting that washes people out and the outdoor noises of feet crunching on gravel or birds chirping that are overly loud. Better editing could have been used to tighten up some scenes, such as the opening one in which we watch Mary run from the front door to the path and back again in what seems like an interminably long time to be watching something so dull and out of focus. There were also sometimes quick cuts from scene to scene, seemingly popping the viewer out of one conversation into an entirely different one with no warning. Most likely due to the poor production values, whenever there was a large party scene, characters that were not the main focus only pretend spoke (i.e., you could see them moving their lips and acting like they were very interested in one another but no words were actually being spoken), which was actually rather distracting at times. Only going through the motions like this gave the feeling the viewer was watching a high school theater performance rather than a professionally done television show.

The adaptation of the novel to screen format itself was for the most part successfully done. With a long miniseries rather than a shorter feature film length, the screenwriters did not have to cut any major parts of the story out, forced to reduce it to just main highlights. Instead, we get all the balls and trips and so on that we see in the novel. The dialogue is largely straight out the book, although occasionally lines were given to different characters in the miniseries than in the novel, which seemed rather odd. This sometimes lead to rather awkward seeming conversations, where the actor seemed to be just reading the line rather than really getting into it. (This could also just be a result of me knowing these lines so well myself now that they don't sound fresh and unrehearsed.) There seemed to be few new lines of dialogue given in this production so if Jane Austen didn't supply a suitable next line word for word, we just jumped to the next scene in that rather quick and jerky way that I mentioned above. At times though, newly introduced monologues for Elizabeth were given as voice-overs, which became rather tedious as the series progressed. Her thoughts seemed rather dithering instead of the lively ones we would come to imagine from the feisty Lizzie. Of all of Austen's female protagonists, Elizabeth seems the least suited for long internal monologues as she is the most outspoken, excepting maybe Marianne Dashwood or possibly Emma Woodhouse. These bouts of introspection seem far more suited to Fanny Price, Anne Eliot, or even Elinor Dashwood.

One good point I will give this adaptation is that it seemed to grasp the humor of Austen's novel a little more than others, which seem to focus more on the dramatic aspects of the book. It was also nice, as always with these adaptations, to see these characters come to life and in particular to see their costumes, dancing, and fine manor houses with lovely grounds. All in all, I enjoyed this adaptation and could even be induced to watch it again. But like many others, I'm still considering the 1995 A&E version of Pride and Prejudice to be favorite my screen adaptation.

Now on to Mansfield Park, which was aired by the BBC just three years later in 1983 (a very good year). This Austen novel is generally not a fan favorite (although I love it), nor is its heroine (but I feel sympathetic toward her). So it has not been adapted near as many times as Pride and Prejudice, with just this miniseries and two movie versions in 1999 and 2007, neither of which I find entirely satisfactory. (Okay, I'll admit it, I basically detest the 1999 version; I'm pretty partial to the 2007 one, but it has a fair share of faults also, including the greatly condensed timeline.) So when this one came up in conversation recently, I thought I had to find it and watch it. When I found it on Netflix, I saw that I had rated this movie and then realized that I had already seen it before. I'm not sure the most glowing recommendation of a miniseries is to discover that one had invested five or six hours to it and didn't recall its existence, even when prompted. But I decided to watch it again and see what I thought of it (again).

To back up, here's the brief description of Mansfield Park for anyone who hasn't read the novel. Young Fanny Price, one of many children in a family of limited means, is sent to live with her wealthy aunt and uncle at their estate, the titular Mansfield Park. Sir and Lady Bertram, her uncle and aunt, have four children of their own - Tom, Edmund, Maria and Julia - who are mainly standoffish toward their young cousin, except Edmund who is always sweet and kind to her. As they grow, Fanny comes to love Edmund as more than a cousin, but he is completely oblivious to this. Meanwhile, Maria is courted by the wealthy but bumbling Mr. Rushworth and Tom spends his life rather frivolously wasting money. Their little world is rather shaken by the introduction into their society of Mr. Henry Crawford and his sister Mary Crawford. Edmund's heart is almost immediately captured by Mary, to Fanny's dismay, and Henry manages to enamor himself to Julia - and the engaged Maria. It's a recipe for a disaster, and hijinks do indeed ensue at Mansfield Park.

Like the 1980 version of Pride and Prejudice, the miniseries of Mansfield Park allows for all the ins and outs of the novel, rather than completely neglecting some parts to force a nearly 500-page novel to fit into an hour and a half long movie. So this version wins points for allowing us to see all that. But while it remains true to the action of the book, we see so little of Fanny's inner thoughts that it loses something. It occurs to me now that while I was well aware of Fanny's feelings the whole time because of my knowledge of Mansfield Park, to the uninitiated it was probably unclear that Fanny was in love with Edmund and felt Mary Crawford was not good enough for him. Unlike Elizabeth Bennet, Fanny so rarely gets to speak her mind that a little narration would be helpful to understand her character and her emotions. It is worth noting that her underlying motivations were so unclear in this film because Sylvestra Le Touzel actually played Fanny the way she was meant to be played - quiet and gentle and meek. So I leave no fault at Ms. Le Touzel's feet but wish that those internal monologues that were so popular in the BBC production of Pride and Prejudice were employed here instead.

In addition to Le Touzel, the rest of the casting was very well done with a few notable exceptions. I had not recalled that the Honourable Mr. Yates was meant to be such a fop, so he seemed over the top to me but perhaps I am remembering his character incorrectly. I was not particularly fond of Nicholas Farrell as Edmund Bertram for he came across as far too smug and self-righteous for my taste. And Jackie Smith-Wood was a travesty as Mary Crawford. For starters, in every scene she was in, I was completely distracted by her short, short hair, which seemed counter to every picture of Regency hairstyles I've ever seen, although apparently some rather daringly fashionable women did have cropped bobs. As Miss Crawford is meant to sporting the latest fashions from London, I could perhaps think the hair and costume department were going for this, but her clothes in many scenes were duller and plainer than those of Maria and Julia. And, the actor herself is not particular attractive and seems a bit old for the part. I know these complaints sound rather superficial and in other circumstances, I would not make them. But recall the source material! Mary Crawford is meant to be so stunningly beautiful and charming that she nearly makes Edmund abandon his high moral ground (and arguably is successful in this on some fronts, such as the play acting or hogging Fanny's pony) and that she is looked up to by Maria and Julia because of her London fashion and air. Ms. Smith-Wood is not capable of fulfilling that role, plain and simple. She does do a pretty decent job at having a lively and pert manner, but I can hardly believe the BBC couldn't find another person who could do that also. Or at the very least give Smith-Wood a more interesting hairstyle and wardrobe.

Despite these few objections (although Edmund and Mary are large parts so not liking these actors was a big deal), I did enjoy the casting choices, as I've mentioned. In particular, I thought Lady Bertram, Tom Bertram, Henry Crawford, Mr. Rushworth, and Susan Price were particularly well suited to their roles. These actors seemed born to play these parts and I'll probably picture them in these roles the next time I read the novel. The Bertram sisters, along with their father and their aunt Norris, also were played by fitting actors. (I do have to note that I found Sir Bertram's badly adjusted wig distracting also, but not as much so as Miss Crawford super short hairdo.) A fun fact is that Jonny Lee Miller has a small part as one of Fanny's younger siblings - not only do I adore Jonny Lee Miller as an actor, but he went on to star as Edmund Bertram in the 1999 film version of Mansfield Park. However, while the casting and acting was overall well done, there were a few moments when the characterizations were a bit overblown. In particular, I'm thinking of the scene in which Fanny Price works herself up into complete hysterics over the idea of marrying Henry Crawford and the one or two scenes where Lady Bertram is not only dozing stupidly on her couch but also sucking her thumb while doing so. Both mannerisms were taking the characters a bit too far into the extreme possibilities for their personalities.

Also similar to the Pride and Prejudice miniseries from the 80s, the production values in 1983's Mansfield Park leave something to be desired. The shaky camera for the conversations within carriages particularly bothered me, although the microphones picking up some sounds more so than dialogue was also irritating at times. This was more of an issue to me here in Mansfield Park than in Pride and Prejudice because for some reason, BBC did not feel the need to include closed captioning for this miniseries. If I really couldn't catch a line of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice, I could rewind and hastily slap on the captions feature to get it but there was no such recourse here. (As I grow harder of hearing all the time, the lack of closed captioning on certain films and TV shows displeases more and more.) At least in this movie, however, they managed to figure out how to allow some background noise in larger party scenes so the actors off to the side could actually murmur to one another rather than doing the peculiar silent lip movement thing they did in Pride and Prejudice. The abrupt scene shift was not really an issue here, except when a particular episode ended. The working model seemed to be to cut the episode off at exactly 52 minutes regardless of where the story might be at that point. There were no good "hooks" so to speak to keep the viewer wanting to come back for the next episode, let alone any sort of satisfying conclusion. One episode ended so abruptly in the middle of a conversation between Henry and Mary Crawford that for a moment I thought the picture froze ... until of course I saw the credits start to roll. I suppose many Austen fans didn't need the extra something to compel them to come back for another episode, but other viewers might have and an episode conclusion that felt at least like the end of a conversation instead of the middle of it wouldn't be an absurd request.

While this version of Mansfield Park is adept at presenting the book in a fairly complete and favorable adaptation and I did enjoy it this time around as well as the first time, I still prefer the 2007 movie as the best available version at this time.

To all those Janeites out there celebrating Pride and Prejudice's big 2-0-0 today, I wish you joy! And I leave you with some questions: What do you think about the BBC's 1980s versions of Austen's novels? Which are your favorite adaptations of Austen's works?

Monday, January 28, 2013

Sunday, January 27, 2013

The Unforgiven: A Thoughtful Western with a Big Finish

In The Unforgiven, Ben heads up the Zachary clan made up of his mother, his two younger brothers Cash and Andy, and his sister Rachel, a foundling that the family brought up as their own. The Zachary family lives an idyllic country Western life with a nice ranch and a cattle partnership covering the basics, and a camaraderie (and occasional courtship) with their neighbors the Rawlins to fill their social needs. That is, until a one-eyed, gray-haired man bearing a saber comes into town and starts rumors that Rachel is actually an Indian, raising all kinds of trouble in this small community.

Despite having Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn in starring roles (as Ben and Rachel, respectively) and John Huston at the helm as director, it seems like this movie hasn't survived the years as well as some other classic films. Note "seems" is the operative word in that sentence. I could be completely off base and it could remain very popular, but I only heard about it when I watched a biography of Audie Murphy, who played Cash in the film. However, both Hepburn and Huston had reasons for distancing themselves from this movie, which I'll talk about below, with Huston reportedly saying it was the only one of his films that he found dissatisfying.

Right off the bat, I should say that I'm not really a huge fan of Westerns. There are some notable exceptions but for the most part I find them rather dull. (The only time I ever fell asleep in a movie theater was while watching 3:10 to Yuma, a movie which pretty much epitomizes everything I dislike about badly done Westerns.) But this movie was very different. Like Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks, this movie was more of a drama that happens to be set in the Wild West and concerns itself more with the pathos of the story and characters than with stereotypical Western machismo and shootouts. However, there was some of the latter in this movie (and in One-Eyed Jacks as well), as I'll discuss later on in this blog post.

One reason this movie was more dramatic than some other Westerns was because Huston, a veteran film director of critical acclaim (and incidentally, the father of actor Anjelica Huston), wanted to make a movie to explore racism in America - a very noble goal. Indeed, the movie is based on a book of the same name by Alan Le May, in which the author apparently discussed white America's hatred of its native people at length. However, the movie's producers were purportedly more interested in profit and desired a more traditional - and less controversial - Western. I presume this is the reason behind the movie definitely being interesting for beginning to shine a light on racism in America - specifically Caucasian Americans' fear and hatred of American Indians - yet leaving the viewer with the feeling that it didn't dig deep enough. It also seemed to undermine its own points at times by containing some rather stereotypical portrayals of the Kiowa tribe.

Nevertheless, I really enjoyed that this movie wasn't just surface level plotting but also contained numerous deeper themes. Besides examining racism and prejudices and their causes, the film is a thoughtful exploration of the meaning of family and family values (i.e., blood vs. adopted family, standing by one's family despite difficult truths, etc.). It also pits community and togetherness versus the questionable ideal of rugged American individualism, a quintessential Western standby. The movie portrays kangaroo courts and the idea of taking justice into one's own hands, which is also a frequently referenced thing in Westerns. And, The Unforgiven also pits against each other two different gender stereotypes: the hyper-masculine response of resorting to violence and death instead of letting quarrels die out naturally versus the nurturing feminine reaction of sheltering a baby and raising her despite past rivalries. It's worth noting that these two "gendered" reactions are not always exclusively the abode of the corresponding sex. Pa Zachary, when he was still alive, was initially the one to take Rachel in to the family fold, and her brothers, especially Ben and Andy, love her unconditionally. And as we see as the movie progresses, Ma Zachary will take her vengeance and is more than capable of handling a gun. (Fun fact: Lillian Gish, the actor playing Ma Zachary, was apparently a remarkable markswoman, more so than the men involved in the project.) Spoiler! Even Rachel totes a gun by the end of the movie and chooses her place alongside her adopted brothers by killing her biological brother in cold blood. All of these themes are presented not in a hit-you-over-the-head kind of way, but in an understated manner throughout the unraveling of the plot.

Likewise, a lot of the character development is unfolded quietly and over time in most cases. The romance between Ben and Rachel was a bit odd considering how they were raised as siblings, but the simmering chemistry between Lancaster and Hepburn was undeniable. And this romance didn't feel entirely tacked on, like in some movies where the hero and the heroine getting together just feels like the cherry on top that came out of the blue, if you pardon the mixed metaphors. Again, it was understated and slowly built over time. It started out innocently enough with Rachel seemingly especially excited by seeing Ben after his return from a long journey to Wichita and back, but the viewer might brush that off as simply a particularly close pair of siblings. The idea of such a romance then is brought up by and laughed off by Rachel and Ben when she says, "I could marry that handsome, winsome Charlie or that baby Jude. I could even marry you. ... Well, why not? We're not cousins. We're not even relatives." to which Ben retorts, "We're not even friends." in a joking manner. Things become more serious when the cattle hand Johnny Portugal reaches up to pull a nettle out from Rachel's hair and Ben's reacts with uncharacteristic anger, leaving the rest of the crowd to mutter that he sure is protective of his sister. The tension is palpable at points like this one.

The characters of Rachel and Ben were particularly compelling as Hepburn and Lancaster displayed excellent acting in this film. Hepburn developed Rachel from a carefree, joyful young girl to a burdened woman filled with pathos and self-sacrificial leanings, making this transformation completely believable along the way. Of course, she sounded more like Holly Golightly than the adopted daughter of a Texas cattle rancher and she seems far too fair-skinned to have anyone question her lineage as being native to the American West, but those things are what they are and the viewer soon gets pulled into the movie enough to overlook them. Like Hepburn, Lancaster expertly took Ben from a joking and loving brother, somewhat burdened by being the family patriarch and main breadwinner, to a torn man making tough decisions with heavy consequences. At the risk of overusing the word, pathos best describes the audience's feeling toward Ben and his actions by the end of the movie. Occasionally, Lancaster mumbled a bit and was thus difficult to understand - especially with his zingers in the beginning of the movie - but this also wasn't enough of a problem to seriously hinder my enjoyment of the film.

As Ben and Rachel were the main focus on the movie, their characters got to be the most fully developed but other characters also had their share of growth as well as a sometimes unclear set of motivations, making them three-dimensional beings. Cash, who started out as the most blatantly racist character of all, gets his chance for redemption and to look beyond his own fears and prejudices. Ma Zachary is a complicated character, as I've already mentioned, who can go from entirely sweet and nurturing to tough as tacks and violent at a moment's notice. She holds the family secret for a long time, managing to lie to her younger children for years in a way that still makes her seem loving and redeemable. (I say her younger children because it's more than obvious that Rachel's past in a complete mystery to Cash, Andy and Rachel herself. But it's unclear how much Ben knew all along; sometimes it seems like he knows all and other times it's possible he was in the dark as well.) Even Abe Kelsey, the saber-toting "villain" of the movie, has a tragic back story that leaves the viewer feeling somewhat sympathetic towards him.

Then, of course, there are times when the movie completely fails at character development. Most notably, there's the absolutely ridiculous character of Georgia Rawlins who all put throws herself at Cash's feet in her efforts to get married to him because that is her one and only goal in life. The other members of the Rawlins family are not well defined, and the relationship between Rachel and Charlie Rawlins never felt like something to be taken seriously as we knew so little about Charlie. His existence seemed more like a way to push the plot forward than anything else. And, as I've mentioned earlier in this post, the characterization of the Kiowa tribe members was anything but fleshed out or three-dimensional. They come in peace but briefly and are otherwise the "savages" of any other stereotypical Western movie.

Still, the movie's promising parts outweigh its flaws. One thing I can't stand is a Western that doesn't take the time to bother showing off the amazing landscapes of the American West. The Unforgiven, while studying complex characters and exploring deep themes, also stops to show off the beauty of the land with sweeping panoramas of gorgeous Western vistas. And, it's not just breathtaking beautiful scenery for its own sake -- the imagery is there to help tell the story in Huston's cinematography. For instance, there is one particularly poignant scene in which we stop and watch an abandoned piano set against a desolate backdrop of dusty land littered with dead bodies. It's an incredibly powerful image and gets to those deeper themes of culture and family versus violence and being alone. I will admit there were a few scenes of cattle and horses that seemed to go on a little longer that I would prefer, but they were also there to help further the story and its characters. In addition, they served to show off the various talents of the actors and extras, although they ended up leading to some personal injuries. While filming, Hepburn broke her back after being thrown from a horse and it's possible this injury later led to a miscarriage. Art has its casualties, too, and it's not pretty.

Being a Hollywood Western film, it's not enough for The Unforgiven to simmer with chemistry and fester with racism. It's almost obligatory that a Western end with a bang - quite literally - and thus we get the climactic ending to this movie. So if extended sequences of gun battles are not your thing, it's at this point that you might want to jump ship on this movie. Spoilers! Granted, this big finale of a final stand-off between the Zacharys and the Kiowa tribe allows for all the family members to show their true colors. But it also leaves all the tribal members dead, which is hardly the ending one would hope for in a movie designed to examine why American settlers and native tribes can't just get along. Considering that the Zacharys' bigger gripe seems to be with the community that refuses to accept Rachel now that they know the truth of her genetics, it seems odd that the family would be forced to fight off the tribe rather than their former friends. The latter might have been the truly controversial end to get audiences in 1960 to start thinking long and hard about prejudices. But instead we have a pretty much stereotypical ending to a Western movie, which is a bit of a letdown after everything else this film has offered.

Still, all in all, I was really rather riveted by this movie and quite enjoyed it. It definitely provides some food for thought, and those are the best kinds of movies in my opinion. (Even if an occasional light-hearted piece is necessary after a long and/or bad day.) I'm now considering watching John Ford's The Searchers, another Western film based on an Alan Le May novel concerning itself with prejudices directed at American Indian tribal members. But meanwhile I will simply say The Unforgiven is a movie that may have gotten dusty on the shelves over the years, but it should definitely be revisited and given a proper place in Hollywood history.

Despite having Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn in starring roles (as Ben and Rachel, respectively) and John Huston at the helm as director, it seems like this movie hasn't survived the years as well as some other classic films. Note "seems" is the operative word in that sentence. I could be completely off base and it could remain very popular, but I only heard about it when I watched a biography of Audie Murphy, who played Cash in the film. However, both Hepburn and Huston had reasons for distancing themselves from this movie, which I'll talk about below, with Huston reportedly saying it was the only one of his films that he found dissatisfying.

Right off the bat, I should say that I'm not really a huge fan of Westerns. There are some notable exceptions but for the most part I find them rather dull. (The only time I ever fell asleep in a movie theater was while watching 3:10 to Yuma, a movie which pretty much epitomizes everything I dislike about badly done Westerns.) But this movie was very different. Like Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks, this movie was more of a drama that happens to be set in the Wild West and concerns itself more with the pathos of the story and characters than with stereotypical Western machismo and shootouts. However, there was some of the latter in this movie (and in One-Eyed Jacks as well), as I'll discuss later on in this blog post.

One reason this movie was more dramatic than some other Westerns was because Huston, a veteran film director of critical acclaim (and incidentally, the father of actor Anjelica Huston), wanted to make a movie to explore racism in America - a very noble goal. Indeed, the movie is based on a book of the same name by Alan Le May, in which the author apparently discussed white America's hatred of its native people at length. However, the movie's producers were purportedly more interested in profit and desired a more traditional - and less controversial - Western. I presume this is the reason behind the movie definitely being interesting for beginning to shine a light on racism in America - specifically Caucasian Americans' fear and hatred of American Indians - yet leaving the viewer with the feeling that it didn't dig deep enough. It also seemed to undermine its own points at times by containing some rather stereotypical portrayals of the Kiowa tribe.

Nevertheless, I really enjoyed that this movie wasn't just surface level plotting but also contained numerous deeper themes. Besides examining racism and prejudices and their causes, the film is a thoughtful exploration of the meaning of family and family values (i.e., blood vs. adopted family, standing by one's family despite difficult truths, etc.). It also pits community and togetherness versus the questionable ideal of rugged American individualism, a quintessential Western standby. The movie portrays kangaroo courts and the idea of taking justice into one's own hands, which is also a frequently referenced thing in Westerns. And, The Unforgiven also pits against each other two different gender stereotypes: the hyper-masculine response of resorting to violence and death instead of letting quarrels die out naturally versus the nurturing feminine reaction of sheltering a baby and raising her despite past rivalries. It's worth noting that these two "gendered" reactions are not always exclusively the abode of the corresponding sex. Pa Zachary, when he was still alive, was initially the one to take Rachel in to the family fold, and her brothers, especially Ben and Andy, love her unconditionally. And as we see as the movie progresses, Ma Zachary will take her vengeance and is more than capable of handling a gun. (Fun fact: Lillian Gish, the actor playing Ma Zachary, was apparently a remarkable markswoman, more so than the men involved in the project.) Spoiler! Even Rachel totes a gun by the end of the movie and chooses her place alongside her adopted brothers by killing her biological brother in cold blood. All of these themes are presented not in a hit-you-over-the-head kind of way, but in an understated manner throughout the unraveling of the plot.

Likewise, a lot of the character development is unfolded quietly and over time in most cases. The romance between Ben and Rachel was a bit odd considering how they were raised as siblings, but the simmering chemistry between Lancaster and Hepburn was undeniable. And this romance didn't feel entirely tacked on, like in some movies where the hero and the heroine getting together just feels like the cherry on top that came out of the blue, if you pardon the mixed metaphors. Again, it was understated and slowly built over time. It started out innocently enough with Rachel seemingly especially excited by seeing Ben after his return from a long journey to Wichita and back, but the viewer might brush that off as simply a particularly close pair of siblings. The idea of such a romance then is brought up by and laughed off by Rachel and Ben when she says, "I could marry that handsome, winsome Charlie or that baby Jude. I could even marry you. ... Well, why not? We're not cousins. We're not even relatives." to which Ben retorts, "We're not even friends." in a joking manner. Things become more serious when the cattle hand Johnny Portugal reaches up to pull a nettle out from Rachel's hair and Ben's reacts with uncharacteristic anger, leaving the rest of the crowd to mutter that he sure is protective of his sister. The tension is palpable at points like this one.

The characters of Rachel and Ben were particularly compelling as Hepburn and Lancaster displayed excellent acting in this film. Hepburn developed Rachel from a carefree, joyful young girl to a burdened woman filled with pathos and self-sacrificial leanings, making this transformation completely believable along the way. Of course, she sounded more like Holly Golightly than the adopted daughter of a Texas cattle rancher and she seems far too fair-skinned to have anyone question her lineage as being native to the American West, but those things are what they are and the viewer soon gets pulled into the movie enough to overlook them. Like Hepburn, Lancaster expertly took Ben from a joking and loving brother, somewhat burdened by being the family patriarch and main breadwinner, to a torn man making tough decisions with heavy consequences. At the risk of overusing the word, pathos best describes the audience's feeling toward Ben and his actions by the end of the movie. Occasionally, Lancaster mumbled a bit and was thus difficult to understand - especially with his zingers in the beginning of the movie - but this also wasn't enough of a problem to seriously hinder my enjoyment of the film.

As Ben and Rachel were the main focus on the movie, their characters got to be the most fully developed but other characters also had their share of growth as well as a sometimes unclear set of motivations, making them three-dimensional beings. Cash, who started out as the most blatantly racist character of all, gets his chance for redemption and to look beyond his own fears and prejudices. Ma Zachary is a complicated character, as I've already mentioned, who can go from entirely sweet and nurturing to tough as tacks and violent at a moment's notice. She holds the family secret for a long time, managing to lie to her younger children for years in a way that still makes her seem loving and redeemable. (I say her younger children because it's more than obvious that Rachel's past in a complete mystery to Cash, Andy and Rachel herself. But it's unclear how much Ben knew all along; sometimes it seems like he knows all and other times it's possible he was in the dark as well.) Even Abe Kelsey, the saber-toting "villain" of the movie, has a tragic back story that leaves the viewer feeling somewhat sympathetic towards him.

Then, of course, there are times when the movie completely fails at character development. Most notably, there's the absolutely ridiculous character of Georgia Rawlins who all put throws herself at Cash's feet in her efforts to get married to him because that is her one and only goal in life. The other members of the Rawlins family are not well defined, and the relationship between Rachel and Charlie Rawlins never felt like something to be taken seriously as we knew so little about Charlie. His existence seemed more like a way to push the plot forward than anything else. And, as I've mentioned earlier in this post, the characterization of the Kiowa tribe members was anything but fleshed out or three-dimensional. They come in peace but briefly and are otherwise the "savages" of any other stereotypical Western movie.

Still, the movie's promising parts outweigh its flaws. One thing I can't stand is a Western that doesn't take the time to bother showing off the amazing landscapes of the American West. The Unforgiven, while studying complex characters and exploring deep themes, also stops to show off the beauty of the land with sweeping panoramas of gorgeous Western vistas. And, it's not just breathtaking beautiful scenery for its own sake -- the imagery is there to help tell the story in Huston's cinematography. For instance, there is one particularly poignant scene in which we stop and watch an abandoned piano set against a desolate backdrop of dusty land littered with dead bodies. It's an incredibly powerful image and gets to those deeper themes of culture and family versus violence and being alone. I will admit there were a few scenes of cattle and horses that seemed to go on a little longer that I would prefer, but they were also there to help further the story and its characters. In addition, they served to show off the various talents of the actors and extras, although they ended up leading to some personal injuries. While filming, Hepburn broke her back after being thrown from a horse and it's possible this injury later led to a miscarriage. Art has its casualties, too, and it's not pretty.

Being a Hollywood Western film, it's not enough for The Unforgiven to simmer with chemistry and fester with racism. It's almost obligatory that a Western end with a bang - quite literally - and thus we get the climactic ending to this movie. So if extended sequences of gun battles are not your thing, it's at this point that you might want to jump ship on this movie. Spoilers! Granted, this big finale of a final stand-off between the Zacharys and the Kiowa tribe allows for all the family members to show their true colors. But it also leaves all the tribal members dead, which is hardly the ending one would hope for in a movie designed to examine why American settlers and native tribes can't just get along. Considering that the Zacharys' bigger gripe seems to be with the community that refuses to accept Rachel now that they know the truth of her genetics, it seems odd that the family would be forced to fight off the tribe rather than their former friends. The latter might have been the truly controversial end to get audiences in 1960 to start thinking long and hard about prejudices. But instead we have a pretty much stereotypical ending to a Western movie, which is a bit of a letdown after everything else this film has offered.

Still, all in all, I was really rather riveted by this movie and quite enjoyed it. It definitely provides some food for thought, and those are the best kinds of movies in my opinion. (Even if an occasional light-hearted piece is necessary after a long and/or bad day.) I'm now considering watching John Ford's The Searchers, another Western film based on an Alan Le May novel concerning itself with prejudices directed at American Indian tribal members. But meanwhile I will simply say The Unforgiven is a movie that may have gotten dusty on the shelves over the years, but it should definitely be revisited and given a proper place in Hollywood history.

Good clean fun with Sherlock Jr.

Many of you may not know this as my entertainment choices have mostly lay elsewhere during the past year or so that I've been writing this blog, but I LOVE old movies. Not crappy 80s movies or trippy 70s movies, but mainly golden era 1940s-1950s movies, with a little crossover into the early 60s or late 30s. Too far into the 60s and things get too "groovy" while too early in the 30s and the production values are horrific, so I generally avoid these. One major exception to these general rules though is anything by Buster Keaton.

I hope I don't have to school anyone on the screen icon Buster Keaton, but just in case here's the basics about him: Buster Keaton was a film actor ala Charlie Chaplin, full of slapstick physical comedy in silent movies (although he did appear in some talkies later in his career, notably Sunset Boulevard and In the Good Old Summertime). Although he didn't have the typical "leading man" qualities of being stunningly handsome and dashing, Keaton always landed a starring role, often in film endeavors in which he also wrote and/or directed. While it's inevitable that he will be compared to Charlie Chaplin (just as I did above), when it comes to physical comedy, Buster Keaton has my vote as the absolute best, bar none. (When we look at their later films outside the silent era, however, Chaplin's dark humor absolutely steals the show for me. Seriously. Go watch Limelight, Monsieur Verdoux, and/or The Great Dictator and then tell me Chaplin wasn't a genius.) What astounds me about Keaton's physical comedy isn't just how purely good it is, but the risks he took to get a laugh. Potential - and actual - injury to himself didn't stop Keaton from any gag that would entertain. And did I mention just how good his comedy is? I'm not usually a fan of the slapstick - I generally find it puerile and often crass. And, some comedic actors will beat a dead horse, with a particular running gag continuing on for so long that it ceases to be funny. But Keaton had perfect timing and acts of physicality that could not help but produce a laugh. His The Cameraman is one of the funniest films I have ever seen, and the public pool scene is perhaps the most hilarious example of physical comedy out there, although Keaton and a monkey filming a shootout in Chinatown together in that same movie is a close contender. And while the physical comedy and slapstick routines are the hallmarks of any Buster Keaton movie from the 1920s, his films don't forget about storytelling and provide a sustainable and interesting storyline (usually a romantic plot), which is no small feat for a silent movie.

What I'm trying to say with that very long introduction is that today I had the pleasure of watching a new-to-me Buster Keaton movie called Sherlock Jr. Like many a Buster Keaton film, it stars him as a down-on-his-luck, sort of clueless but incredibly kind man who is head over heels in love with a pretty young woman who another more polished man tries to woo. In Sherlock Jr., Keaton's nameless protagonist wants to become a detective but currently works as a projectionist in a movie theater. When he falls asleep there one day while a movie plays in the background, he dreams himself into the movie. The movie-within-the-movie is called Hearts and Pearls and involves a woman's pearl necklace being stolen by a pair of thieves, one of whom is pretending to court her. Keaton's character arrives on the scene as famed criminologist Sherlock Jr. whose trusty sidekick is a fellow named Gillette. Sherlock Jr. and Gillette elude the criminals' attacks and manage to save the pearls and the girl by the end of the film-within-the-film. Of course, this being a Buster Keaton movie, all of this happens with numerous ridiculous - but funny - gags along the way, including a cross-dressing Keaton, a driver-less motorcycle, and a booby-trapped house.

Meanwhile, in the real world, Keaton's character is barely scrapping together enough money to present gifts for his girlfriend and is eventually accused of a theft he didn't commit. The initial evidence is against him, but his intrepid girlfriend figuratively takes a page out of his detective's handbook and tracks down additional evidence to clear his name. And, of course, this second plot includes some running jokes involving a sticky newspaper, a slippery banana peel, and one lost dollar that several people try to claim, to name a few.

All in all, Sherlock Jr. has so many different jokes and comedic situations that it's bound to hit the mark with the audience at least some of the time. There were a few gags, like the sticky newspaper, that fell a little flat for me, but mostly I was thoroughly entertained by this movie. It didn't reach The Cameraman heights of ridiculously hysterical, laugh-out-loud funny, but it was more than capable of producing plenty of laughs.

The movie is also notable for its use of special effects. As per usual with Buster Keaton, many of the gags ran the risk of physical injury and apparently Keaton actually broke his neck in the production of this film during one of his physical comedy routines. Some other scenes also left me feeling a bit squirmy, worried about the actor's safety. (However, the fact that this actor is long dead and that I knew he survived the silent film era allowed me to enjoy the physical comedy rather than be made too uncomfortable.) But even more notable to me were the scenes involving Keaton's movie-within-the-movie. This sequence starts off with us seeing Keaton's character asleep in the projectionist's booth and then we watch his dream self rise up out of his body, put on his hat, and head out the door. Did I mention this movie came out in 1924?! I had no idea the kind of technology needed for such a scene was available. (C'mon, they couldn't figure out how to add sound to movies yet.) After this amazing feat, we watch his character travel down the movie theater aisle and up on to the stage before walking into the screen itself. Again, this in in 1924. Keaton, who directed this movie as well as starred in it, was apparently not only a comedic genius but also incredibly talented at making movie magic.

I'm not sure if I've emphasized enough yet that this movie was made in 1924. ;) While the humor certainly transcends the time period, there were so many elements that made this movie feel almost stereotypically old-timey. The movie-within-the-movie's female lead has flapper fashion chic, the men's everyday wear includes cravats and spats, steam engine locomotives seem almost ubiquitous in the background, and Tin Lizzies rattle by on the streets. At one point there's even gangsters standing on the car's sideboards, hanging on to the "speeding" car while trying to shoot down the protagonist ahead of them, in what feels like a classic old-fashioned movie scene.

All in all, Sherlock Jr. is a great movie for good clean humor, a sweet romantic story, old-timey fun, and mind-boggling special effects given the time period. And all this is just under 45 minutes. Did I mention that Buster Keaton was a genius?

I hope I don't have to school anyone on the screen icon Buster Keaton, but just in case here's the basics about him: Buster Keaton was a film actor ala Charlie Chaplin, full of slapstick physical comedy in silent movies (although he did appear in some talkies later in his career, notably Sunset Boulevard and In the Good Old Summertime). Although he didn't have the typical "leading man" qualities of being stunningly handsome and dashing, Keaton always landed a starring role, often in film endeavors in which he also wrote and/or directed. While it's inevitable that he will be compared to Charlie Chaplin (just as I did above), when it comes to physical comedy, Buster Keaton has my vote as the absolute best, bar none. (When we look at their later films outside the silent era, however, Chaplin's dark humor absolutely steals the show for me. Seriously. Go watch Limelight, Monsieur Verdoux, and/or The Great Dictator and then tell me Chaplin wasn't a genius.) What astounds me about Keaton's physical comedy isn't just how purely good it is, but the risks he took to get a laugh. Potential - and actual - injury to himself didn't stop Keaton from any gag that would entertain. And did I mention just how good his comedy is? I'm not usually a fan of the slapstick - I generally find it puerile and often crass. And, some comedic actors will beat a dead horse, with a particular running gag continuing on for so long that it ceases to be funny. But Keaton had perfect timing and acts of physicality that could not help but produce a laugh. His The Cameraman is one of the funniest films I have ever seen, and the public pool scene is perhaps the most hilarious example of physical comedy out there, although Keaton and a monkey filming a shootout in Chinatown together in that same movie is a close contender. And while the physical comedy and slapstick routines are the hallmarks of any Buster Keaton movie from the 1920s, his films don't forget about storytelling and provide a sustainable and interesting storyline (usually a romantic plot), which is no small feat for a silent movie.

What I'm trying to say with that very long introduction is that today I had the pleasure of watching a new-to-me Buster Keaton movie called Sherlock Jr. Like many a Buster Keaton film, it stars him as a down-on-his-luck, sort of clueless but incredibly kind man who is head over heels in love with a pretty young woman who another more polished man tries to woo. In Sherlock Jr., Keaton's nameless protagonist wants to become a detective but currently works as a projectionist in a movie theater. When he falls asleep there one day while a movie plays in the background, he dreams himself into the movie. The movie-within-the-movie is called Hearts and Pearls and involves a woman's pearl necklace being stolen by a pair of thieves, one of whom is pretending to court her. Keaton's character arrives on the scene as famed criminologist Sherlock Jr. whose trusty sidekick is a fellow named Gillette. Sherlock Jr. and Gillette elude the criminals' attacks and manage to save the pearls and the girl by the end of the film-within-the-film. Of course, this being a Buster Keaton movie, all of this happens with numerous ridiculous - but funny - gags along the way, including a cross-dressing Keaton, a driver-less motorcycle, and a booby-trapped house.

Meanwhile, in the real world, Keaton's character is barely scrapping together enough money to present gifts for his girlfriend and is eventually accused of a theft he didn't commit. The initial evidence is against him, but his intrepid girlfriend figuratively takes a page out of his detective's handbook and tracks down additional evidence to clear his name. And, of course, this second plot includes some running jokes involving a sticky newspaper, a slippery banana peel, and one lost dollar that several people try to claim, to name a few.

All in all, Sherlock Jr. has so many different jokes and comedic situations that it's bound to hit the mark with the audience at least some of the time. There were a few gags, like the sticky newspaper, that fell a little flat for me, but mostly I was thoroughly entertained by this movie. It didn't reach The Cameraman heights of ridiculously hysterical, laugh-out-loud funny, but it was more than capable of producing plenty of laughs.

The movie is also notable for its use of special effects. As per usual with Buster Keaton, many of the gags ran the risk of physical injury and apparently Keaton actually broke his neck in the production of this film during one of his physical comedy routines. Some other scenes also left me feeling a bit squirmy, worried about the actor's safety. (However, the fact that this actor is long dead and that I knew he survived the silent film era allowed me to enjoy the physical comedy rather than be made too uncomfortable.) But even more notable to me were the scenes involving Keaton's movie-within-the-movie. This sequence starts off with us seeing Keaton's character asleep in the projectionist's booth and then we watch his dream self rise up out of his body, put on his hat, and head out the door. Did I mention this movie came out in 1924?! I had no idea the kind of technology needed for such a scene was available. (C'mon, they couldn't figure out how to add sound to movies yet.) After this amazing feat, we watch his character travel down the movie theater aisle and up on to the stage before walking into the screen itself. Again, this in in 1924. Keaton, who directed this movie as well as starred in it, was apparently not only a comedic genius but also incredibly talented at making movie magic.

I'm not sure if I've emphasized enough yet that this movie was made in 1924. ;) While the humor certainly transcends the time period, there were so many elements that made this movie feel almost stereotypically old-timey. The movie-within-the-movie's female lead has flapper fashion chic, the men's everyday wear includes cravats and spats, steam engine locomotives seem almost ubiquitous in the background, and Tin Lizzies rattle by on the streets. At one point there's even gangsters standing on the car's sideboards, hanging on to the "speeding" car while trying to shoot down the protagonist ahead of them, in what feels like a classic old-fashioned movie scene.

All in all, Sherlock Jr. is a great movie for good clean humor, a sweet romantic story, old-timey fun, and mind-boggling special effects given the time period. And all this is just under 45 minutes. Did I mention that Buster Keaton was a genius?

Sunday, January 20, 2013

Best Books of 2012

Sadly, I haven’t been updating this blog as much as I would like lately, although I’ve been doing plenty of arts and entertainment things I would love to tell you all about … someday.

Last year,

I managed to be on time for a change and got in under the wire with my

end-of-the-year roundup of everything I had been reading. This year,

however, I have been particular neglectful

of this blog and even though I was keeping notes on what I thought were the

best books I read this year, I’m only just now finally culling that list.

Let it be

noted that while I’m calling this the best books of 2012, most – if not all –

of these books were written prior to that time period. It’s just that I finally

got around to reading these books during 2012.

Unlike last

year, I read very few young adult novels this year, so I collapsed children’s

and YA books into one category, listed here underneath the adult books I read.

Graphic novels and nonfiction books are indicated by these symbols

respectively: ^ and **. Any books that I was re-visiting for a second read are

marked with a (2) after the title.

Hopefully

anyone reading this blog and looking to tackle that next read can glean some

new titles from this list. Each title is hyperlinked to my review of it on

LibraryThing for anyone looking for more information on that particular book.

Adult books

1984 (2) by

George Orwell

The Adventures

of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Batman: The Long

Halloween^ by Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale

Batman: Year One

by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli

The Beach

Bum’s Guide to the Boardwalks of New Jersey** by Dick Handshuch and Sal

Marino

Cranford

(2) by Elizabeth Gaskell

The Collected

Poems by Sylvia Plath

The Colossus

and Other Poems by Sylvia Plath

Frankfurt

Pocket Guide** by Thomas Cook Publishing

Fried Green

Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café (2) by Fannie Flagg

The Greater

Journey: Americans in Paris** by David McCollough

The Hypnotist

by Lars Kepler

A Little Bit

Wicked: Life, Love, and Faith in Stages** by Kristin Chenoweth with Joni

Rodgers

Mr. Monk Goes

to the Firehouse by Lee Goldberg

Neptune Noir:

Unauthorized Investigations into Veronica Mars** edited by Rob Thomas

Psych: A Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Read by William Rabkin

Psych: A Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Read by William Rabkin

Psych: Mind

Over Magic by William Rabkin

The Question:

Pipeline^ by Greg Rucka and Cully Hamner

Sleeper:

Season 1^ by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips

Sleeper:

Season 2^ by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips

Winter Trees

by Sylvia Plath

What I Did

by Chris Wakling

Children’s/YA books

Being Teddy

Roosevelt by Claudia Mills and R.W. Alley

Biblioburro: A True Story from Colombia** by Jeanette Winter

Biblioburro: A True Story from Colombia** by Jeanette Winter

A Boy Called

Dickens** by Deborah Hopkinson and John Hendrix

Boys of Steel:

The Creators of Superman** by Marc Tyler Nobleman

Chicka Chicka

Boom Boom by Bill Martin, Jr. and John Archambault

Fannie in the

Kitchen: The Whole Story from Soup to Nuts of How Fannie Farmer Invented

Recipes with Precise Measurements by Deborah Hopkinson and Nancy Carpenter

The Great and

Only Barnum: The Tremendous, Stupendous Life of Showman P.T. Barnum** by

Candace Fleming

Knuffle Bunny:

A Cautionary Tale by Mo Willems

Library Lily

by Gillian Shields and Francesca Chessa

A Little Princess

(2) by Frances Hodgson Burnett

Lives of

Extraordinary Women: Rules, Rebels (and What the Neighbors Thought)** by

Kathleen Krull and Kathryn Hewitt

Mice and Beans

by Pam Munoz Ryan and Joe Cepeda

Peek-a-Baby: A

Life-the-Flap Book by Karen Katz

The Penny Pot

by Stuart J. Murphy and Lynne Woodcock Cravath

Tickle Time! by Sandra Boynton

Where Is Baby’s Birthday Cake? by Karen Katz

Tickle Time! by Sandra Boynton

Where Is Baby’s Birthday Cake? by Karen Katz

Where the Wild

Things Are (2) by Maurice Sendak

**

= nonfiction

(2) = re-read

^ = graphic novel

(2) = re-read

^ = graphic novel

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)